ONE HUNDRED YEAR OF THE RUSSIAN NEP – LESSONS FOR CUBA

By: Samuel Farber, April 3, 2021

Author’s Note – This article originally appeared

in Spanish in La Joven Cuba (Young Cuba), one of the most important

critical blogs in the island, where the Internet remains the principal vehicle

for critical opinion because the government has not yet succeeded in

controlling it. The article elicited some strong reactions including that of a

former government minister who called it a provocation.

The New Economic Policy (NEP) introduced by the revolutionary government in

1921 was in fact an attempt to reduce the widespread discontent among the

Russian people with measures designed to increase production and popular access

to consumer goods. Even though the Civil War (1918-1920) caused great hardship

among the rural and urban populations, it was the politics of War Communism,

introduced by the Bolshevik government during that period, that significantly

worsened the situation. This led to a profound alienation among those who had

been the pillars of the October Revolution in 1917: the industrial workers, and

the peasantry that constituted 80 percent of the population.

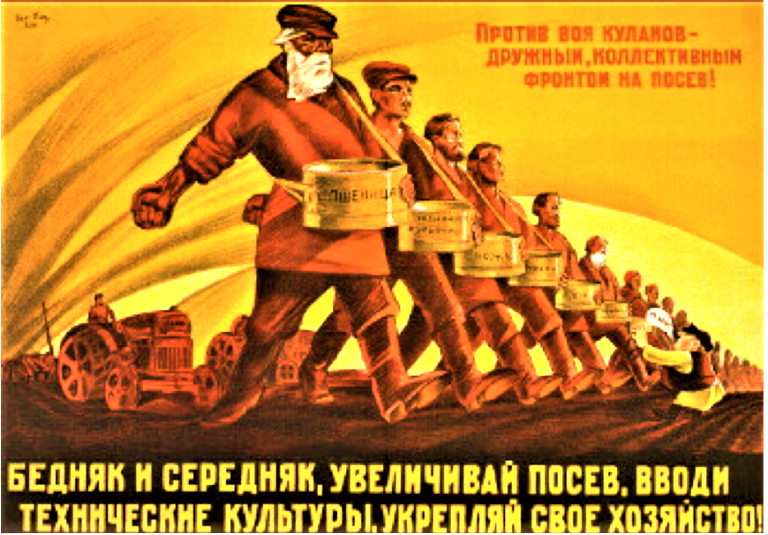

In the countryside, the urban detachments, organized to confiscate from the

peasantry their agricultural surplus to feed the cities, ended up also

confiscating part of the already modest peasant diet in addition to the grain

needed to sow the next crop. The situation worsened when under the same policy

the government, based on an assumed class stratification in the countryside

that had no basis in reality, created the poor peasant committees (kombedy)

to reinforce the functions of the urban detachments. Given the arbitrary

informal and formal methods that characterized the operations of the kombedy,

these ended up being a source of corruption and abuse, frequently at the hands

of criminal elements active in them, who ended up appropriating for their own

use the grain and other kinds of goods they arbitrarily confiscated from the

peasantry.

Moreover, during the fall of 1920, symptoms of famine began to appear in the

Volga region. The situation became worse in 1921 after a severe drought ruined

the crops, which also affected the southern Urals. Leon Trotsky had proposed in

February 1920, to substitute the arbitrary confiscations of War Communism with

a tax in kind paid by the peasantry as an incentive to have them grow more

surplus grain. However, the party leadership rejected his proposal at that

time.

The politics of War Communism was also applied to the urban and industrial

economy through its total nationalization, although without the democratic

control by the workers and the soviets, which the government abolished when the

civil war began and replaced with the exclusive control from above by state

administrators. Meantime, the workers were subjected to a regime of militarized

compulsory labor. For the majority of the Communist leaders, including Lenin,

the centralized and nationalized economy represented a great advance towards

socialism. That is why for Lenin, the NEP was a significant step back.

Apparently, in his conception of socialism, total nationalization played a more

important role than the democratic control of production from below.

The elimination of workplace democracy was only one aspect of the more general

clampdown on soviet democracy that the Bolshevik government launched in

response to the bloody and destructive civil war. Based on the objective

circumstances created by the war, and on the urgent need to resolve the

problems they were facing, like economic and political sabotage, the Bolshevik

leadership not only eliminated multiparty soviets of workers and peasants, but

also union democracy and independence, and introduced very serious restrictions

of other political freedoms established at the beginning of the

revolution.

***************************

***************************

The Situation in Cuba

Since the

decade of the nineties, and especially since Raúl Castro assumed the maximum

leadership of the country in 2006–formally in 2008 – economic reform has been

one of the central concerns of the government. The logic of that

economic reform points to the Sino-Vietnamese model–which combines an

anti-democratic one-party state with a state capitalist system in the

economy–and not to the compulsory collectivization of agriculture and the

five-year plans brutally imposed on the USSR by Stalinist totalitarianism after

the NEP. The Cuban government’s decision to authorize the creation of the PYMES

(small and medium private enterprises), a decision frequently promised but not

yet implemented, would constitute a very important step towards the establishment

of state capitalism in the island. This state capitalism will very probably be

headed by the current powerful political, and especially military, leaders who

would become private capitalists.

Until

now, the Cuban government has not specified the size that would define the

small and especially the mid-size enterprises under the PYMES concept. But we

know that several Latin American countries (like Chile and Costa Rica) have

defined the size in terms of the number of workers. Chile, for example, defines

the micro enterprises as those with less than 9 workers, the small-size with 10

to 25 workers, the medium-size with 25 to 200 workers, and the big size with

more than 200 workers. Should Cuba adopt similar criteria, its mid-size

enterprises would end up as capitalist firms ran by their corresponding

administrative hierarchies. If that happens, it is certain that the official

unions will end up “organizing” the workers in those medium size enterprises

and, as in the case of Chinese state capitalism, do nothing to defend them from

the new private owners.

Regarding

political reform, there has been much less talk and nothing of great importance

has been done. As in the case of the Russian NEP, the social and economic

liberalization in Cuba has not been accompanied by political democratization

but, instead, by the intensification of the regime’s political control over the

island. Even when the government has adopted liberalizing measures in the

economy, like the new rules increasing the number of work activities permitted

in the self-employed sector, it continues to ban private activities such as the

publication of books that could be used to develop criticism or opposition to

the regime. This is how the government has consolidated its control over the

major means of communication –radio, television, newspapers and magazines –

although it has only partially accomplished that with the Internet.

The

government is also using its own socially liberalizing measures to reinforce

its political control. For example, at the same time that it liberalized the

rules to travel abroad, it developed a list of “regulated” people who are

forbidden to travel outside of the island based on arbitrary administrative

decisions, without even allowing for the right of appeal to the judicial system

it controls. Similar administrative practices lacking in means for judicial

review control have been applied to other areas such as the missions organized

to provide services abroad. Thus, the Cuban doctors who have decided not to

return to the island once their service abroad has concluded, have been victims

of administrative sanctions – eight years of compulsory exile – without any

possibility of lodging a judicial appeal.

Still

pending is the implementation of the arbitrary rules and the censorship of

artistic activities of Decree 349, that allows the state to grant licenses and

censor the activities of self-employed artists. The implementation of the

decree has been postponed due to the numerous and strong protests that it

provoked. All of these administrative practices highlight the fact that the

much discussed rule of law proclaimed by the Constitution is but a lie. Let us

not forget that the Soviet constitution that Stalin introduced in 1936 was very

democratic … on the paper it was written. Even so, Cubans in the island should

appeal to their constitutionally defined rights to support their protests and

claims against the Cuban state whenever it is legally and politically

opportune.

At the

beginning of the Cuban revolutionary government there was a variety of

political voices heard within the revolutionary camp. But that disappeared in

the process of forming the united party of the revolution that established the

basis for what Raúl Castro later called the “monolithic unity” of the party and

country. That is the party and state model that emulates, along with China and

Vietnam, the Stalinist system that was consolidated in the USSR at the end of

the twenties, consecrating the “unanimity” dictated from above by the maximum

leaders, and the so-called “democratic centralism”, which in reality is a

bureaucratic centralism.

The Cuban

Communist Party (CCP) is a single party that does not allow the internal

organization of tendencies or factions, and that extends its control over the

whole society through its transmission belts with the so-called mass

organizations (trade unions, women’s organization), institutions such as the

universities, as well as with the mass media that follow the “orientations”

they receive from the Department of Ideology of the Central Committee of the

CCP. These are the ways in which the one-party state controls, not necessarily

everything, but everything it considers important.

The

ideological defenders of the Cuban regime insist in its autochthonous origins

independent from Soviet Communism. It is true that Fidel Castro’s political

origin is different, for example, from that of Raúl Castro, who was originally

a member of the Socialist Youth associated with the PSP (Partido Socialista

Popular), the party of the pro-Moscow orthodox Communists. But Fidel

Castro developed his “caudillo” conceptions since very early on, perhaps as a

reaction to the disorder and chaos he encountered in the Cayo Confites

expedition in which he participated against the Trujillo dictatorship in the

Dominican Republic in 1947, and with the so-called Bogotazo in Colombia in

1948.

In 1954,

in a letter he wrote to his then good friend Luis Conte Aguero, Fidel Castro

proclaimed three principles as necessary for the integration of a true civic

movement: ideology, discipline and especially the power of the leadership. He

also insisted in the necessity for a powerful and implacable propaganda and

organizational apparatus to destroy the people involved in the creation of

tendencies, splits and cliques or who rise against the movement. This was the

ideological basis of the “elective affinity” (to paraphrase Goethe) that Fidel

Castro showed later on for Soviet Communism.

So, what

can we do? The recent demonstration of hundreds of Cubans in front of the

Ministry of Culture to protest the abuses against the members of the San Isidro

Movement and to advocate for artistic and civil liberties, marked a milestone

in the history of the Cuban Revolution. There is plenty of room to reproduce

this type of peaceful protest in the streets against police racism, against the

tolerance of domestic violence, against the growing social inequality and

against the absence of a politically transparent democracy open to all, without

the privileges sanctioned by the Constitution for the CCP. At present, this

seems to be the road to struggle for the democratization of Cuba from below,

from the inside of society itself, and not from above or from the outside.

The

lesson of the Russian NEP is that economic liberalization does not necessarily

signify the democratization of a country, and that it may be accompanied by the

elimination of democracy. In Cuba there has been economic and social

liberalization but without any advance on the democratic front.

Comments

Comments for this post are closed.